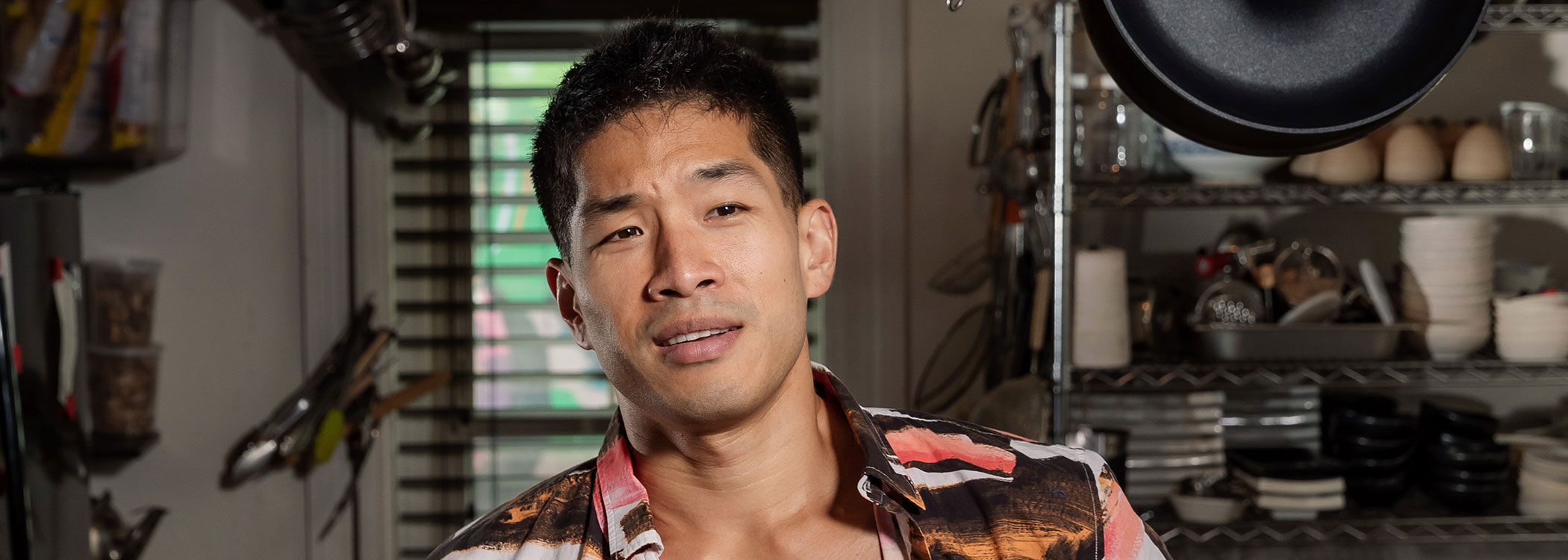

Chef & Tiktok Star Jonathan Kung On Creating Identity Through Third-Culture Cooking

By Stephanie Gravalese

Jonathan Kung is a Detroit chef and TikTok personality known for his food and cooking videos. Before the pandemic, Kung ran an underground kitchen space in Detroit’s Eastern Market. Kung describes himself as a “third-culture cook”—referring to the in-between space where different cultures meet and, through cooking, create a new identity. Kung is currently working on his first cookbook with Clarkson Potter.

“Third-culture cooking” is a term I thought of connected with the term “third-culture kid”—also known as global nomads. A third-culture kid is somebody who has an established culture at home—the culture of their parents, the culture of their family, the places they live—but then they’re removed from that in their greater world, in the sense that their home might be of one culture, but then the country of which that home resides is completely different.

For example, any Chinese-American, Mexican-American, or Nigerian-American are all certainly American kids, but it can get more complicated than that. There is that separation, where you never fully fit in a place, which is not necessarily bad. People like us are shown to have, for example, a greater capacity for empathy because we’re so used to different forms of communication.

If you grew up in a household where a parent often cooked the food of their home culture, you will understand the tastes and flavors and the ingredients even though you might not be able to read the label on the jar. But you might be able to recognize the jar. And if you ever went into an ethnic grocery store, say 15 years later, and you see that jar, and you’re like, “I don’t know what this is, but it used to be in my house.”‘

I was raised in Toronto as a Canadian, and I eventually went back to Hong Kong during my high school ages. I went from a place where people did not look like me to one where almost everybody did, but at the time, I didn’t relate to them. I still had a missing piece, a strangeness. Not to say that my experience in Hong Kong was bad–it was amazing. But I didn’t feel like I was ever a part of a place where my home was, wherever I lived. And so those are some really pretty typical common feelings that third-culture kids have.

So third-culture cuisine is like an informed fusion of cooking. I don’t really like the term “fusion” because it was made a little dirty by the food that came out of the 90s. Third-culture cuisine is more informed and nuanced because it comes from a person with a deep understanding of both types of cuisine that person is trying to combine. I think it’s most exciting type of cuisine to come out of countries that are very diverse, such as the United States and Canada, where people are interested in cultural exchange.

When the United States was going through its own kind of culinary renaissance with gastropubs and New American restaurants, they were mostly helmed by white men. What they were doing was picking and choosing from surface-level interesting things from diverse sources within the country. When I was younger, and all that was happening, it triggered certain emotions in me—protectionist, gatekeeper-y feelings that I felt strongly about. Then, later on, as I matured as a cook, I realized what I should have been doing was not stopping them from doing what they were doing. I should have been doing what they were doing, and then use my basis in Chinese cuisine as my own addition to it.

Taking part in the diversity of the American culinary landscape is not something that only white people should have access to. Every cook of every culture in this country should have access. That’s why I wanted to show these cross-cultural dishes I was doing, but at the same time sharing my vision so that other people who have their own cultures, and who have stories similar to mine, will use that as a basis with their own cultural dishes—as a starting point to try something different. Third-culture cuisine just requires somebody to look for connections between different people. That’s what makes it a lot of fun, and that’s what makes it kind of familiar.

I came to this conclusion as a result of a creative identity crisis. I went back to Hong Kong a lot for a while, and I saw what it is like to cook Chinese food there. I learned that my perceptions of Chinese food—traditional Chinese cooking, banquet cuisine and stuff like that, which I was teaching myself—was not what Chinese food meant over there. I was learning such outdated out-of-fashion things, and people there were doing much more interesting things, but still staying within the realm of traditional Cantonese cuisine.

I was kind of embarrassed with my idea of myself as a Chinese cook versus the reality. I had to learn a little bit of the culinary history of Chinese food within America to realize that this was me trying to chase authenticity and traditionalism. That was never going to happen all the way from here in Detroit because I wasn’t willing to move back to Hong Kong to learn it. So what can I do over here, or who can I learn from over here that would set me apart from the people over there?

I wasn’t really interested in learning from the big restaurants. I was more interested in learning from people who, even though they don’t look, speak, or cook like me, have a similar experience to mine. Having that feeling of that connection is a good starting point. I set out to learn and to incorporate cultural dishes that oftentimes had also been stigmatized, because I feel like cooking with empathy is like the difference between cooking for yourself and cooking and serving others.

From there, I started looking for similarities between cuisines. I would just look at the most subtle things, like Chinese zongzi, which are bamboo leaves wrapped around rice that often hold a salted egg yolk, and some sausage and pork belly, and it’s steamed. I noticed how similar those are to tamales. They’re both starches that hold things steamed inside the leaves and husks of other things. So I’d explain zongzi to a Mexican person as “Chinese tamales.”

I started to come up with other combinations based on cultural similarities, instead of just throwing two things together. I was looking for what somebody from another culture might recognize. This type of cooking does not have to be complicated. I’m more than happy to show off my skills and creativity as a cook, but I think it’s so much more fun to do things that have that same creativity and same basis of being diverse, but in ways that almost everyone can do. You can make pasta using dried noodles in a jar, and you can make frozen Chinese dumplings with pesto.

When it comes to my videos talking about culinary appropriation, a lot of people may not realize that my sense of gatekeeping is probably more liberal than they expect. I’m kind of anti-gatekeeping for a lot of things. “Cook our food but respect the people” is the message that I have been going with for the past few years. I got a lot of duets and stitches on Tiktok from people trying out my ideas. A lot of people were very receptive to them, saying, “This was kind of obvious. Why didn’t anyone think of this before?”

And then there were some dismissive comments, like, “Well, this guy just invented ravioli, again.” I was like, “Well, no, no, not really. You just don’t really know the nuances of a Chinese dumpling versus a ravioli.” The fact that I still see new comments about those videos to this day means people still talk about them.

It’s often within our own communities where we attack ourselves. One of the reasons I think that happens is because there is this underlying guilt from being so othered as kids, so shamed for eating the foods that we did, for having the customs that we did. We might have been embarrassed by these things as children, so maybe we shunned them until we realized in our adult life that these things were valuable.

So if there was a specific dish that our grandma made for us, and then we see somebody else—possibly someone who looks like us—cooking it differently, we get super defensive. A person might say, “That’s not how you make it. You’re totally inauthentic. You’re not doing it right. That’s not how that dish is done.” When in fact, that person isn’t an expert about the food, they’re just an expert about their memory. Through that guilt and embarrassment and shame, they lash out, and they want to claim what little hold they still have on those really important memories.

As a person who has been very active on social media, I see the cycles and the patterns of everything, how people jump on these things. It happens year by year, generation by generation. The stories seem to repeat themselves, especially for folks in POC communities. I’m not saying it’s a tired story, but we have to harness it into something a little different. That’s my personal belief. Embracing diversity from a third-culture perspective is me taking ownership of what I like. I’m not fully a person from Hong Kong. I’m not fully Chinese or Chinese-American. What does that mean? What does that mean to me? If I were to cook my identity, what does that look like? By doing this, I’m taking ownership of my identity, and I take ownership of my narrative and my creative output as a result.

A lot of people who are the most outspoken gatekeepers about food barely know how to cook. So what are they guarding? I’m not diminishing people’s pain. I’m just questioning whether or not the way that they handle that pain is probably the most effective way to do it. Therapy can be delicious, too.